One of the interesting challenges you run into as a game developer is how to simply and clearly describe your game to people who encounter it for the first time. The 10-second hook, or the “elevator pitch.” Sum it up in one sentence. What is your game?

Gone Home is a simulation of exploring an abandoned house to discover the story of the people who lived there.

Like any elevator pitch, your one-sentence description should get people asking more questions. What I’d like do here is answer the question “what does ‘simulation’ mean in Gone Home?” Because the answer to that question drives our entire design philosophy behind the game.

Mechanically, our biggest video game inspirations come from the subgenre of “Immersive Simulations”: Ultima Underworld, System Shock, Thief, Deus Ex, BioShock, the upcoming Dishonored. These are first-person games that emphasize believable gameworlds and player-driven experience. Explore how you want, develop the playstyle you want, inhabit a world that functions in convincing, internally-consistent ways. Immerse yourself in the experience as if you “really are” the character in the game.

These games also all center around combat (or, often, avoiding combat.) Many of the interesting systems and player choices come from how you interact with enemies, and how you customize your own abilities to do so. But there are no enemies in Gone Home; there are no other people at all.

So how does the philosophy of Immersive Simulation apply to a game with no combat? Can a “non-violent Immersive Sim” even exist? For us, it comes down to extracting the specific definition of “simulation” as it applies to the games that inspire us, and applying that to the context of experience we’re presenting in Gone Home.

Because “simulation” in our case is not a literal term. It’s not virtual reality or the Holodeck (or even Jurassic Park Trespasser.) What it means is allowing the player to do whatever their character might logically do within the game’s context, and ensuring that the gameworld reacts in the way you expect. The design challenges in pursuit of this goal involve deciding what to abstract away from literal simulation, and how best to accomplish it.

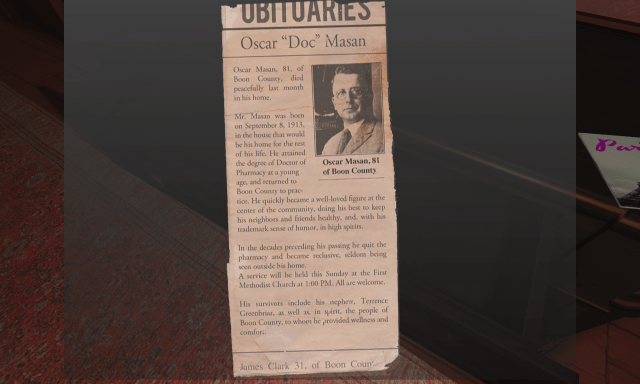

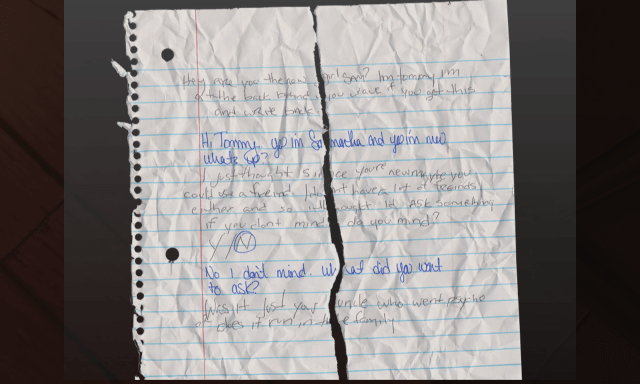

This all starts from considering the role of the player character. In Gone Home you are a normal person in an abandoned house, trying to figure out what happened to the people who lived there. So what might you want to do in pursuit of that goal? Walk through the house, open doors and drawers and closets and cabinets. Read things. Pick up objects and examine them for clues.

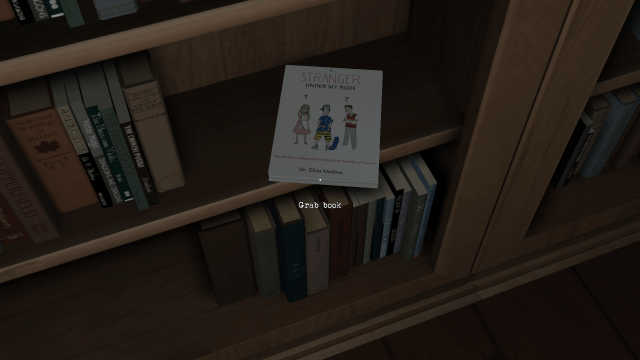

Interesting design questions start to arise at this point. For instance, you want to be able to “read things,” but in the context of the game, what things do we make “readable”? A single-family home tends to contain hundreds of books. Allowing the player to literally read every single one of them would be bad both player-experientially, raising the text noise-to-signal ratio way above acceptable levels, and production-wise, as implementing and maintaining thousands of pages of text just wouldn’t be practical for us.

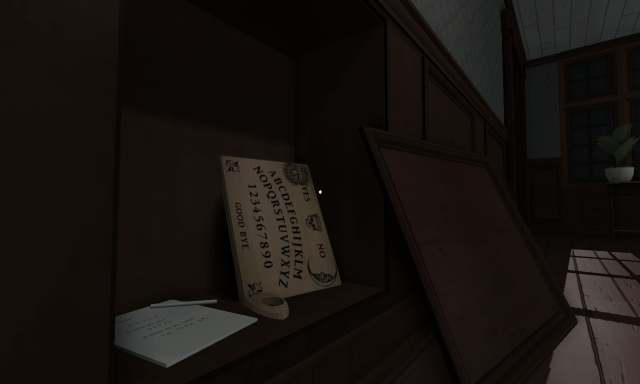

This is where the idea of abstraction via consistent visual language comes into play. In Gone Home, you can pick up and examine any book that is lying out on its own, and cannot interact with any book that is jammed into the lineup of a bookshelf.

Quickly an implicit contract is established: any book you see lying out on its own will be relevant to the story and characters, and will be interactable; anything stuffed into a bookshelf will not be interactable, but also will not be relevant to uncovering the mystery of the house. Abstraction occupies the space where the rules of the game deviate from the rules of the real world; abstracted rules must always be clear and consistent, and help the player to more fluidly inhabit the role of the character they’re playing.

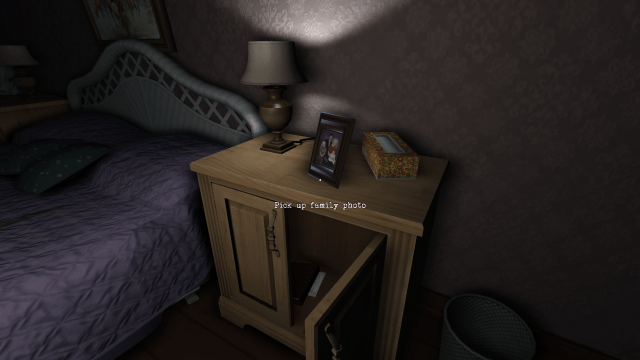

The question of how the player interacts with physics objects gets a little more interesting, and a little more challenging from a systems standpoint. It starts with a similar type of filtering as the book problem: if you’re an explorer trying to figure out what happened in this house, your character wouldn’t need to rearrange the furniture or topple bookshelves. But she might want to pick up smaller objects on tabletops or inside cabinets to look for evidence underneath them, or to pick up specific objects to examine them more closely. To support this player role, we implemented the Physics Examine and Put Back systems.

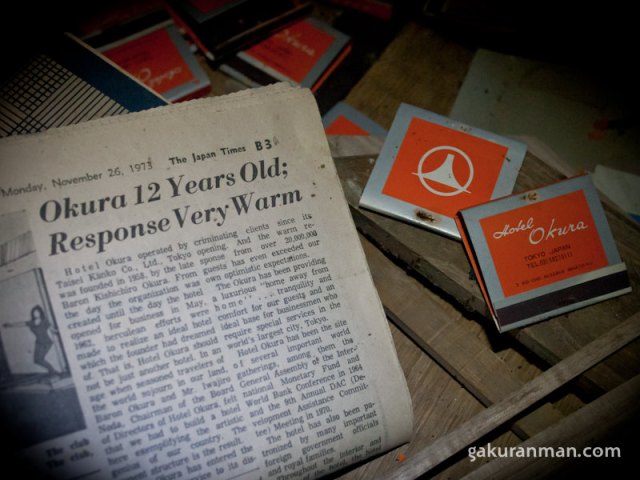

The Physics Examine system allows the player to grab any small physical object in the game and rotate it to look at it from different angles. This keeps the idea of “examining objects” within the same interactive mode as walking around exploring the house, and puts all physics objects on a level interactive playing field; you can examine a totally mundane pencil the same way you’d examine a matchbook with a portentous note scrawled on it. You don’t get to look at only specific physics objects in high detail “because the designer says so”; you can closely examine any physical object that YOU suspect might be relevant to your experience.

This only got us halfway there, though. What happens when you want to put the object down? At first we only had a system where you toss the object back at the world, turning you into a clumsy vandal by default. Which felt really bad and dumb. The player character in Gone Home might want to pick something up, look at it, then put it back down carefully. But we also wouldn’t want to restrict the player to ONLY be able to pick up objects and put them back where they came from. If the player WANTS to toss stuff everywhere, by all means they should be able to. But it shouldn’t be the only option.

Our initial ideas for design solutions were way too complicated and impractical, entailing a system that would allow the player to place any physics object precisely on any surface, arranging arbitrary objects just so, dynamically detecting valid placements and rotations in realtime, etc. Eventually we realized that this wasn’t supporting the role of the player as investigator, but our own desires as blue sky designers of a literal simulation, which is not what Gone Home is about.

Instead we implemented the Put Back system, whereby any object that has been placed intentionally before your arrival (anything from a desktop picture frame to a bottle of handsoap) can be “put back” in its original location by pointing at its original spot and clicking to place the object. If you look anywhere else while holding the object, you toss it into the world.

So if you want to put back everything you find right where you found it, you’re free to; if you want to grab all the mugs and books and photo frames that are placed around the house and pile them up in a corner, you can do that too. But YOU’ve made that decision, and have the freedom to do so with any object you pick up. We’ve provided authored possibilities to the player, to support inhabiting the role of the player character, but we do not dictate that the player must comply with them.

To us, that is the essence of Immersive Simulation: giving the player all the interactive tools they might desire in the pursuit of inhabiting the player character’s role, without ever saying “you HAVE to play this way, or make this decision, or engage with this content.”

The difference between Gone Home and its inspirations is what role you inhabit: not a gene-spliced assassin or cyborg superagent, but a normal person in an unfantastical, everyday locale. Gone Home is an invitation. Come to this simulated place, explore as much or as little as you want, get as much out of it as you put in. “Playing how you want to” can mean more than choosing to sneak past a guard instead of killing him, or upgrading run speed instead of jump height. It can mean inhabiting a familiar, virtual place “the way you really would if you were there,” engaging with the experience how you want to, if you want to, immersing yourself as deeply as you choose into this particular slice of interactive experience.

We only hope that we can live up to our inspirations.